International private jet arrivals into the United States increasingly involve passengers traveling under the Visa Waiver Program using ESTA rather than traditional visitor visas. While ESTA is widely understood in the airline environment, general aviation operations face a different compliance landscape.

For U.S.-based flight crews, dispatchers, and international operations teams, the risk is not theoretical. Incorrect assumptions about ESTA eligibility, operator authorization, or CBP procedures can lead to denied boarding abroad, ramp holds on arrival or forced last-minute diversions to alternate ports of entry.

Unlike airline operations, private aviation places much of the compliance responsibility directly on the operator and flight crew. This makes early verification critical, especially when passengers are not traveling with traditional U.S. visas.

ESTA basics and why private aviation is treated differently

ESTA stands for Electronic System for Travel Authorization. It is not a visa. It is an electronic authorization that allows eligible nationals from Visa Waiver Program countries to travel to the United States for business or tourism stays of up to 90 days.

Approval of ESTA does not guarantee admission. Final entry authorization is always made by a CBP officer at the port of entry. From a crew standpoint, this means that documentation must be correct before departure, but passenger admissibility is still subject to inspection upon arrival.

Where private aviation differs from airline operations is not the ESTA itself, but how the flight is categorized and who is responsible for compliance. Commercial airlines operate under standardized carrier agreements with U.S. authorities. Private operators do not automatically fall under that same framework.

For flight crews, this means ESTA use on private aircraft is not only about passenger eligibility. It is also about whether the operator meets the requirements to transport Visa Waiver Program travelers.

This distinction becomes operationally important when flights originate outside the United States. If documentation is incorrect, the issue is usually discovered at departure or upon arrival, when options are limited and schedules are already committed.

Operator status and passenger eligibility must align

One of the most frequent sources of confusion in international business aviation is the assumption that ESTA eligibility depends solely on passenger nationality. In reality, the operator’s authorization status is just as important.

To carry ESTA passengers into the United States, the aircraft operator must be recognized as a Visa Waiver Program signatory carrier. This requirement applies to both U.S.-based operators and foreign operators conducting international private flights.

If the operating company is not approved as a signatory carrier, ESTA cannot be used. In those cases, passengers must hold a valid U.S. visitor visa, typically a B1 or B2, even if they are nationals of Visa Waiver Program countries.

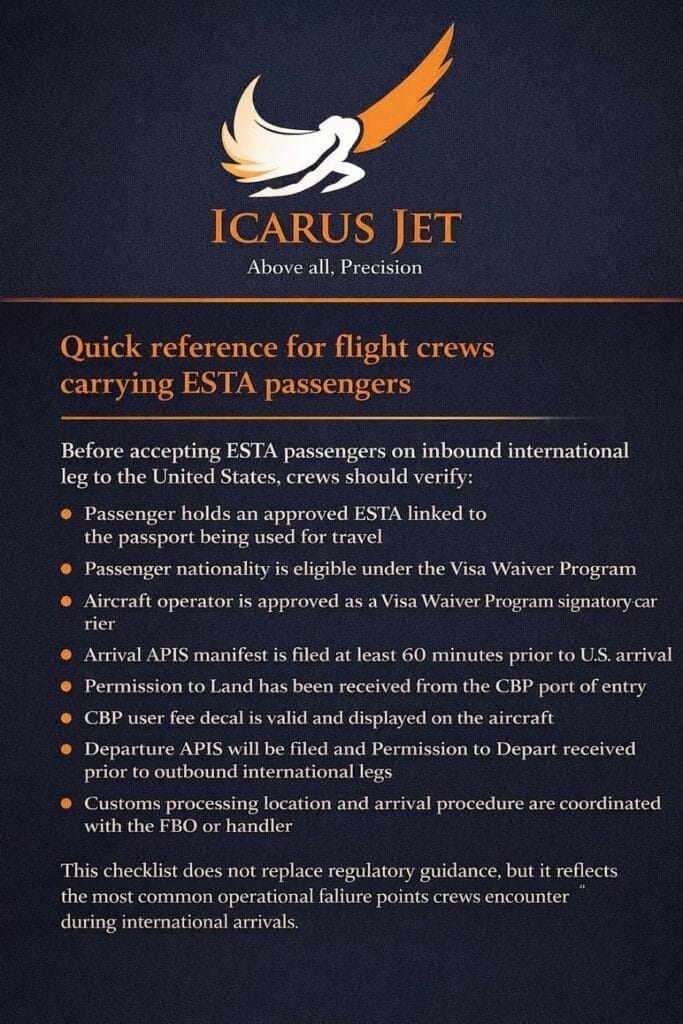

From a crew planning perspective, this creates a non-negotiable verification step. Operator status should be confirmed during dispatch planning and not assumed based on previous international operations.

Passenger eligibility still matters independently. Only citizens of participating Visa Waiver Program countries may use ESTA. Passengers from non-participating countries must obtain a visa regardless of aircraft type, routing, or operator authorization.

Even when nationality is eligible, ESTA approval must be active and linked to the passport used for travel. Crews should verify that passengers are not traveling on newly issued passports that are not associated with existing ESTA authorization.

CBP reporting, clearance procedures, and operational risk

International private aviation comes with specific CBP reporting requirements that directly affect flight legality.

Advance Passenger Information System filing is mandatory for both inbound and outbound international flights. The manifest must include accurate passenger and crew passport data and must be submitted electronically at least 60 minutes prior to arrival into the United States. A separate APIS submission is required prior to departing the United States.

Filing APIS alone does not authorize arrival. Crews must also obtain explicit Permission to Land from the CBP port of entry before departing the foreign location. This process varies by airport but usually involves direct coordination with the CBP office at the arrival airport.

For outbound legs, Permission to Depart is also required. After submitting the departure APIS manifest, crews must receive confirmation from CBP before taking off. Skipping this step is a common compliance mistake during quick-turn international departures.

Another operational requirement is the CBP user fee decal. Most private aircraft arriving from outside the United States must carry a valid decal tied to the aircraft registration. This is an annual requirement and should be checked during trip planning, particularly on aircraft that do not routinely operate international routes.

Charter operators may also be subject to additional inspection fees related to Customs, Immigration, and agricultural processing. These fees are separate from the user fee decal and can affect trip cost calculations and client billing.

Upon arrival, private aircraft must taxi to the designated CBP inspection location, typically a general aviation customs ramp or approved FBO facility. Passengers and crew will undergo passport inspection, ESTA verification, and standard CBP questioning.

From an operational standpoint, crews should brief passengers in advance about inspection procedures and potential waiting times. This is especially important at high-volume ports of entry where CBP staffing, and arrival congestion can vary significantly.

Why ESTA compliance is part of flight risk management

In private aviation, immigration compliance is often viewed as paperwork. In practice, it directly affects mission execution.

Incorrect assumptions about ESTA eligibility can lead to denied boarding abroad, forcing crews to delay departures or reposition aircraft without passengers. On arrival, missing permissions or documentation errors can result in ramp holds, secondary inspections, or diversions to alternate airports with available CBP staffing.

There is also reputational impact. Passengers flying privately expect efficiency and predictability. Immigration delays reflect on the operator and the flight crew, regardless of where the error originated.

For crews, ESTA verification should be treated the same way as crew legality, weather planning, fuel requirements, and alternates. It is part of international operational risk management.

Building ESTA and CBP verification into standard dispatch workflows reduces the likelihood of last-minute surprises. This includes early confirmation of operator status, passenger documentation review, APIS submission timelines, and coordination with ground handlers and CBP offices.

Consistency is what prevents problems. Crews who apply the same compliance checks on every international trip experience fewer operational disruptions.

Do you still have questions? Contact our trip support professionals today.

FAQs

Can passengers use ESTA on any private jet flight into the United States?

No. ESTA may only be used when passengers are traveling on private aircraft operated by a company approved as a Visa Waiver Program signatory carrier. If the operator is not approved, passengers must hold a valid U.S. visa.

Does ESTA guarantee entry into the United States?

No. ESTA authorizes travel under the Visa Waiver Program, but final admission is always determined by a CBP officer at the port of entry.

How early must APIS be filed for international private flights?

APIS must be submitted at least 60 minutes prior to arrival into the United States. A separate APIS filing is required prior to departing the United States.

Do private Part 91 flights still require Permission to Land and Permission to Depart?

Yes. Both private and charter operations must obtain CBP clearance. Permission to Land is required before inbound international departures, and Permission to Depart is required before leaving the United States.

What happens if an operator is not a VWP signatory carrier and passengers only hold ESTA?

Passengers will not be eligible to enter the United States using ESTA. In most cases, they will be denied boarding at departure or refused entry on arrival and will need to obtain a U.S. visa.